There was cake, balloons and congratulations as yet another colleague proudly announced her exciting baby news.

Of course I was pleased for her, but I could see what everyone in the room was thinking, and it made me shudder: ‘It will be Katrina next.’

Oh no it wouldn’t. If there was one thing I was certain of, it was that I would never be having children.

This wasn’t out of a deep-seated fear of childbirth, revulsion for babies or even a jealous guarding of an idyllic, responsibility-free life. It was because my own relationship with my mother had been so bad, and the damage wrought so traumatic, that I couldn’t risk the chance of passing the trauma on to another generation.

I hadn’t even hit my teens before I made the decision. I was too frightened that if I did have a child, I’d end up turning into a mother like her.

While the word ‘mother’ conjures up feelings of love, warmth and security for some, it invokes fear, self-loathing and insecurity in me.

That’s why I’ve blocked my mother from my life. For the best part of ten years there have been no phone calls, messages or birthday and Christmas cards.

She’s 87 now and living alone since the death of my father in 2022, but I’ll probably be the last to know when she goes.

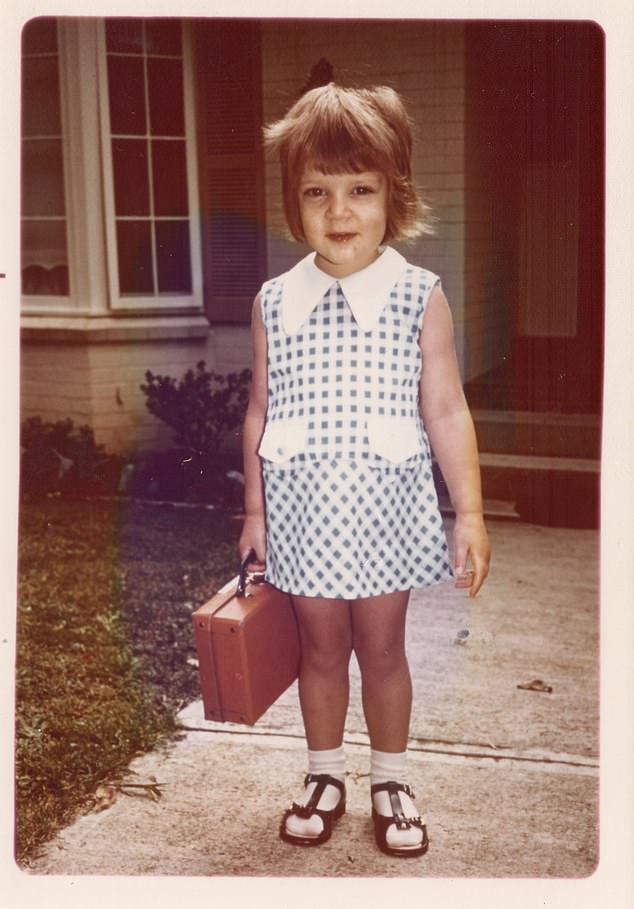

Growing up in Sydney, Katrina felt she could never do anything right in her mother’s eyes

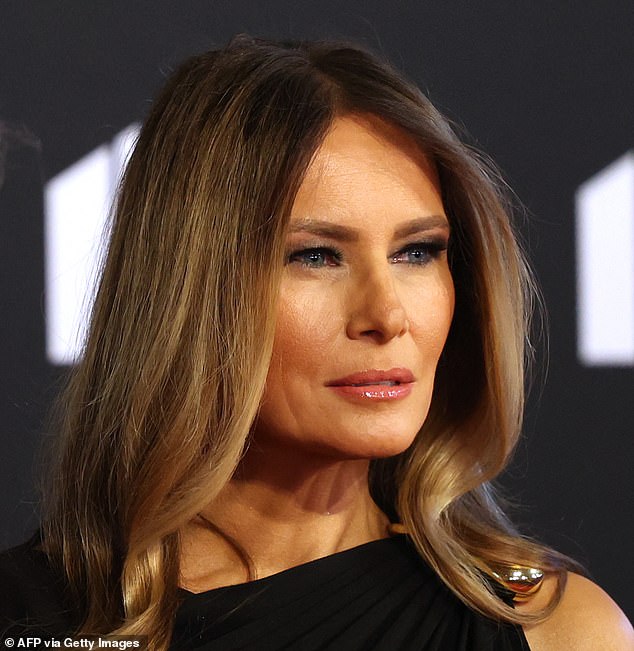

Katrinawrote a memoir showing it is possible to safely face your trauma and create your own happiness

I know people will be shocked at reading this. Normally when I confess that I don’t speak to my mother, the general reaction is: ‘But she’s your mum!’ I’m sure if I described having this kind of toxic relationship with a boyfriend, however, they’d tell me to run and never look back.

So why should it be different with your mother? After all, a major study published this week showed that experiencing verbal abuse as a child can be as damaging to one’s mental health in adulthood as physical abuse.

Growing up in Sydney, I felt I could never do anything right in Mum’s eyes. I would bring my school report card home shaking with terror – it wouldn’t matter if I’d got 99 out of 100, that one dropped mark made me feel I was never good enough.

I lived in constant fear, worrying about the potential repercussions of upsetting her – and, as a result, I adapted all my emotions to Mum’s moods, putting her needs and wants before mine.

She was, in my opinion, a textbook narcissist: deeply insecure, she couldn’t handle criticism or being ’embarrassed’ in public.

One of my earliest memories is throwing a tantrum at nursery during pick-up time and refusing to leave (yes, I know that alone speaks volumes). It’s an incident no doubt familiar to many parents, and one usually shrugged off with a roll of the eyes or a gentle nudge towards the car.

But when we got home, my mum was so angry that I’d embarrassed her in front of the other parents. Her rage was truly terrifying. I can still remember quaking. She controlled me and my three older siblings with those rages. The four of us dealt with targeted abuse separately, but we all endured manipulation and constant criticism.

The impact persists to this day, and my relationship with my siblings is still complicated.

Speaking as a knowledgeable adult, not a cowed child, I think Mum was trying to control us because, internally, she was out of control herself and with a difficult childhood of her own.

Katrina, pictured, lived in constant fear, worrying about the potential repercussions of upsetting her mother

As for my father, it was easy for me to put him on a pedestal and demonise my mother – he didn’t scream or shout like she did – but over time I realised that his enabling of her behaviour, the way he never intervened, was just as damaging.

He’d dismiss her behaviour with a casual ‘you can’t change your mother’. He also worked long hours and was rarely around when things got really bad.

But then he also had his own issues. He too had a traumatic childhood, being adopted into a violent, abusive family when his own mother died. A pattern of bad parenting had been set generations ago, its toxicity spreading like ripples. No wonder I wanted to put a stop to it by not having children of my own.

Its effect lasted well beyond my childhood. I left school at 17, went to university, failed and got kicked out and then started working as a bank teller at 19.

I finally left home at 21 to move in with a friend, but was an emotional mess. Riddled with insecurities I slept around and let everyone trample over me.

As the saying goes, you marry – or, in my case, date – your unfinished business. It’s common for people who’ve been through narcissistic relationships to end up attracting more of them.

I went straight into an abusive relationship with a violent and controlling man for 18 months, despite his ex-girlfriend’s warnings. I had to call the police after one particularly savage beating and secured a restraining order against him – yet I still felt I was the one to blame.

I worked at the bank for about five years and, aged 27, met the kindest, loveliest man. But when we announced our engagement, Mum sneered at my ring and called us ‘hypocrites’ because we were living together. Her words had me sobbing and curled up into a ball.

I sabotaged that lovely relationship. I treated him appallingly and called off the wedding six weeks before the big day. Looking back, he probably had a lucky escape.

I later married another man, a classically trained singer, at the age of 32, whom I met at a friend’s wedding in Chicago. We eloped, seeking a drama-free day that was just about us, and then moved to London. Mum’s reaction? She told me my husband was too good for me, which again felt like a physical punch.

My husband didn’t want children for his own reasons, so that was never part of the discussion. There was another side to me not wanting a family, however, beyond fearing what kind of mother I might be.

I’d always so felt so trapped growing up that I didn’t want to trap myself for 18 years raising a child. Freedom felt so precious and I didn’t want to let it go. Mum, of course, called me selfish for not having children.

Living thousands of miles away from Australia meant contact was infrequent, but every so often Dad would reach out and we’d reconnect, only for the whole process to start over again.

I remember my mother went through a phase of sending nasty emails, pointing out my so-called failings as a daughter.

One day, when I’d had enough, I cited some of them back to her (she was an expert at gas-lighting, so I needed evidence) and she turned the whole argument back to me, calling me vindictive for keeping the messages.

Against this backdrop, my marriage lasted 15 years – a remarkable achievement – before we went our own ways, very amicably.

I had lunch with my family in 2015 and, at the end of a miserable meal, Mum handed me my childhood photo albums. It felt like a symbol of her not wanting me in her life. By this stage, I was done with her emotionally, and I didn’t inform her that I’d be cutting her out from then on.

I last saw Mum for 20 minutes in 2022, after Dad died, when she made a last-ditch attempt to pick a fight – I didn’t take the bait. I’ve blocked her number, and she doesn’t have my email. It’s better that way.

I’m not the only one not talking to her – she has a tricky relationship with all her children – yet she can’t see that she’s the epicentre of it all.

Although I do sometimes feel sorry for her, I know we can never make each other happy.

A lot of people tell me I need to forgive her. But if I called Mum to say this, she’d reply ‘For what?’

Aged 40, I began therapy and discovered that I have complex PTSD due to childhood trauma. Over the last 12 years, as I’ve started to recover, I’ve also embraced meditation and spiritual healing methods.

I decided to write a memoir showing it is possible to safely face your trauma and create your own happiness. I’ve gone from utter self-loathing to someone who’s happy, full of self-love, kindness and self-compassion – and if I can do it, anyone can.

As told to Deborah Cicurel. The Damage Of Words: A Memoir Of Healing Self-Hate And Gaining Self-Mastery by Katrina Collier (£10.99,amazon.co.uk) is out now